Kenya’s anti-gay laws lead to harassment, LGBQ persons say, want change

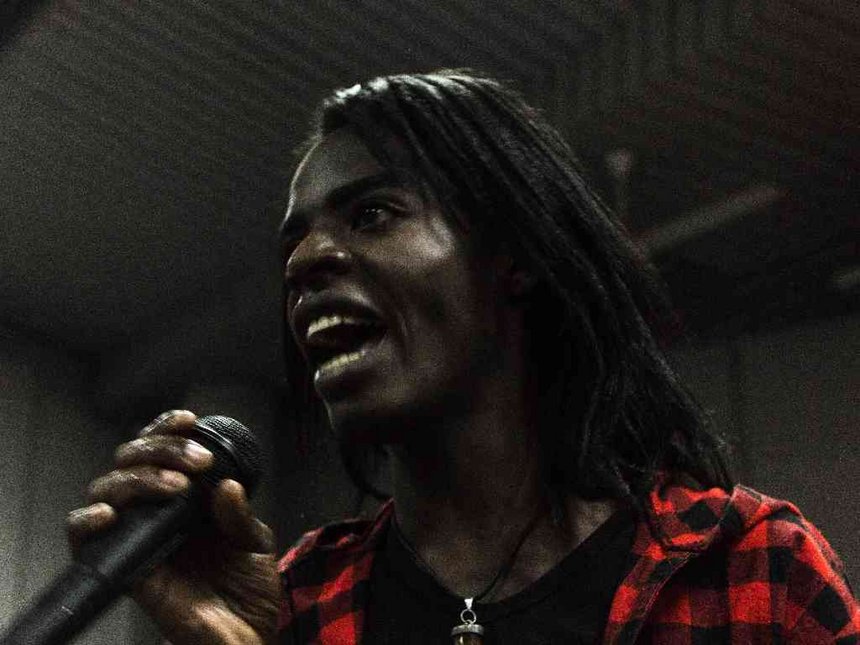

Activist and musician Joji Baro (George Barasa) hides his shoulder-length hair under a grey mavin. The 25 year-old likes to put make-up on his delicate face and walk with a bit of a strut.

But Joji Baro chose boyish clothes today and admits that he cannot fully express himself when he is around Kenyans.

“What I fear most is that I am very cute. When I wear make-up, I fear how the public will react when they see that I am too beautiful to be a man,” he explains.

He identifies as a gender non-conformist, saying he answers to either he or she, and adding that he has had several run-ins with the public because of this. His fear makes him overly cautious when navigating public spaces.

LGBQ rights groups say sexual minorities often come into conflict with the public, including law enforcers, who use Kenya’s anti-homosexuality and petty offences laws to harass members of the gay community in both public and private spaces.

Earlier this year, a case was filed by rights groups and activists, including an Anglican priest, to challenge the government to protect LGBQ people from harassment and violence.

Laws allowing moral policing

Same-sex acts are outlawed under Kenya’s penal code which provides a sentence of up to 14 years for what the law terms as “indecent” or ‘unnatural’ acts.

In 2014, National Assembly Majority leader Aden Duale tabled a list of 595 cases which had been reported and prosecuted under the penal code since 2010.

A 2013 report by the Pew Research Center states that 90 per cent Kenyans believe homosexuality should not be accepted in society.

Reverend Mark Otieno, who is part of the case to repeal sections of the penal code criminalising same sex acts, says he has witnessed several incidents of violence against gay people because of these laws.

“I have witnessed people who have been raped so that their sexual orientation can be corrected. I also counsel people who have been chased away from communities for showing affection to the members of the same gender, he says.

“At one point I had to handle a case of a man who was living with a fellow man whose house was set ablaze by his neighbours. Police arrived before they were lynched but they were still arrested for committing an unnatural act.”

Jackson Otieno, programmes officer at the Gay and Lesbian Coalition of Kenya (GALCK), says the laws lead to moral policing and harassment of sexual minorities and violations of human rights.

“What these laws do is give anybody justification for moral policing. Most of the time ignorant people are arrested using these laws. It leads to profiling, where on some nights, arrests are made in clubs and other spots that LGBQ people frequent,” says Otieno.

He adds that gay people live in fear, which leads to exploitation from both members of the police and the public through extortion.

“Of course a smart prosecutor will not take you to court on a charge of homosexuality. But people go through the process of being put in the cell and being bailed out due to a combination of fear and an ignorance of the law., he says.

Victims charged with petty offences, not homosexuality

Joji Baro says gay people arrested in public are usually charged with petty offences such as loitering or being drunk and disorderly, but not homosexuality.

“When I first came to Nairobi after being disowned by my family for being gay in 2011, I was arrested with a group of friends after purchasing tickets at a bus company on one night. They told us we were loitering and demanded a bribe,” he says.

He says movement at night is especially hard for young gay people as they can easily be accused of prostitution, leading to arrests or extortion by the police.

“When a gay person is seen in public, it is as if they should be committing some kind of crime. We are arrested and charged with petty crimes just so that they can see us go through the legal procedures,” he adds.

Activist Mary Muthui says when LGBQ people are harassed, it is difficult for them to get help.

Muthui was evicted from her home in 2013. Her son found a poster on the door announcing that all gay people must move out of the premises.

She moved fearing for her safety, before she could formally be kicked out. But she lost all her belongings and efforts to report the matter to police only led to more harassment.

“When I arrived at the police station with my girlfriend, the officer asked which one of US was the husband in the relationship,” she says.

Muthui adds that the officer asked whether or not she would feel aroused if he touched her.

“I believe that in this country… that everyone has the right of freedom of speech and expression as well as the right to move freely without any discrimination. But I am yet to find police willing to defend this right,” she says.

Otieno says the case filed in June asks courts to declare sections 162 and 165 of the penal code unconstitutional so that LGBQ persons can be safe.

“GALCK believes the laws criminalising homosexual acts would not exist if the constitution was aligned,” he says.

“The alignment of the penal code and the constitution is our main aim as the existence of these laws creates an environment of violence and fear for sexual minorities from all quarters.That is all we want to stop.”

The Reverend hopes the petition will compel the government to protect sexual minorities.

“The penal code and the articles of our constitution are in conflict when addressing issues of LGBQ persons. My hope is that there will be a change that permits people of all orientations to associate without fear of prosecution or public attacks,” he says.

First published by The Star